Once again, Starship’s We Built This City was voted the worst song of the eighties. My husband, Pete Sears, who was in Starship, agrees with the assessment for the same reason critics and ex-fans seem to hate it so much. In fact, he didn’t really play bass on the damn song. Starship’s new producer at the time, Peter Wolf (not the singer—the Austrian producer, fabricator of hit pop songs and sounds) had Pete sample his bass notes into a sequencer computer and then play the bass part on the synthesizer keyboard—a snyclavier. The core of the drums was also coming out of a machine, although Donny was allowed to overdub toms and cymbols. Pete came home from the studio fuming. He hated it. That album, Knee Deep In The Hoopla was the end of Starship for him.

As a much sought after young musician in the early seventies, he played on all Rod Stewart’s English albums, including Every Picture Tells A Story, which has been voted one of the top 100 best albums ever made in the same Rolling Stone poll that put We Built This City in its place.

We were living in England where Pete was playing with some of the world’s greatest musicians and he was constantly receiving offers to form bands with top-notch people. Among these people were Paul Kantner and Grace Slick, who called weekly from California to try to persuade him to come back to America and form a new band that would be called Jefferson Starship. Pete had a lot of options…but just as Rod Stewart’s Smiler album was finishing, my sister decided to get married and I wanted to go home for her wedding. Pete had liked Jefferson Airplane and felt that with the line-up Paul and Grace were describing, they could make a kick-ass band. We came home for the wedding and Paul and Grace had a limo waiting for us. They had booked us into The Sea Cliff Inn and on our first day back we went to see them at their house on the ocean cliff that overlooked the Golden Gate Bridge. Pete and Grace spontaneously wrote a song together (Hyperdrive) and it sounded like the birth of a band to me.

JEFFERSON STARSHIP in the mid-seventies became one of the top five touring bands in the world. Critics of Starship seem to forget that pre-pop Starship, there was a killer rock band called Jefferson Starship that rocked stadiums and produced guitar and bass solos during sets that rivaled the Grateful Dead in length and improvisation. The songs were individualistic and varied, and each member of the band had equal say. Although that format can lead to in-house fighting, it can also bring out the best in everyone involved. Miracles, a huge hit, was not a contrived song. Marty put a lot of heart into that vocal and you could feel it. The albums were an eclectic jumble and the audience loved them.

Then the riot in Germany happened in 1978, and Grace left the band for much-needed rehab. Marty was blown away by the riot and the interpersonal squabbling (not with Pete), so he also left…which meant the band had to find a new lead singer. Pete had a fabulous soul singer in mind, but Mickey Thomas was ultimately chosen for the job. He had great technique and could certainly hit the high notes that the record company wanted to hear.

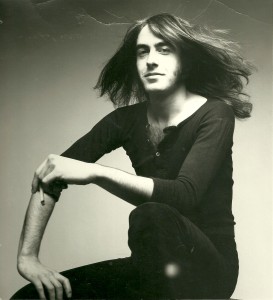

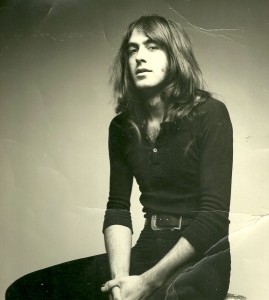

Because Grace was gone, Pete started bringing in songs we had written together. Some people were surprised to learn I was a lyricist, but not anyone who knew me even a little. I remember we were at a party at David & Joan Getz’s house, and someone commented on how great it was that I had started writing. David (who was in Janis Joplin’s original band Big Brother and The Holding Company, and who is the ex-husband of one of my best friends), piped up and said, “Jeannette didn’t just start writing—she was constantly writing back in the sixties when she was staying with Nancy and me—she’s always been a writer.” I was so grateful to him for that comment. He was right of course. In fact, Pete and I first got together in 1972 to write songs. I had a lot of poetry and was trying to turn it into lyrics, and Pete can write music at the drop of a dime, so he invited me over to the house Nicky Hopkins had rented for him in Mill Valley (Pete was going to play bass and occasional double keyboards in a band he was forming).  I went there armed with lyrics, but as we sat together on the piano bench, something else started happening too. Ever see any photos of Pete from that era? Heart-stopping, to say the least.

I went there armed with lyrics, but as we sat together on the piano bench, something else started happening too. Ever see any photos of Pete from that era? Heart-stopping, to say the least.

Sitting on a piano bench with this man...

Long story short, we continued to write together, but it wasn’t until Grace left the band that it felt appropriate to bring in our work. Pete had a great rapport with Grace and enjoyed writing with her, but when she left the band, it was natural for him to turn to me for lyrics. Grace was an amazing lyricist…a tough act to follow, but I never looked at it like that. I’ve always felt that there is room for everyone–in art and in life–there is enough to go around and everyone has something unique to offer. When Pete brought our songs in to the band, they were well received. In fact, Craig asked me to start writing with him too, and David also mentioned that we should get together. The lyrics I wrote with Craig were basically just supplements to his ideas, but the songs Pete and I had written, and were writing, were straight from the heart. Fading Lady Light was about an acid trip I’d had in Joshua Tree. Pete had written the music much more Rolling Stones style than the slant the producer ultimately put on it, but at least Mickey’s vocals still had a soul element at that time. The other song Pete and I contributed to Freedom At Point Zero, Awakening, was a long psychedelic piece with rather esoteric lyrics about a spiritual awakening. The words were sparse—the music took you on the journey that the words described—nothing pop or contrived about it—avant-garde, if anything.

For the album, Modern Times, Pete and I wrote a song called Alien. We had both been reading Sci Fi non-stop for years and this song was our chance to play with the theme. Our other two songs, Save Your Love and Stranger, were also about as far from pop as you could get. Save Your Love was my reaction to the beginning of yuppiedom—a plea to hold onto the things that matter—spiritual values…your ability to love. Stranger was a psychological take on transformation and individualization, with a spiritual base. Grace was back with the band and she sang those lyrics as if she understood them through her very bones. She is an intuitive person with a razor sharp intellect and obviously, a great musical talent.

Okay, I’ve gone off on a tangent. I’ll stop…. I could walk you through all the Jefferson Starship and Starship albums and give you my take on things, but I started out to write about We Built This City from the Knee Deep In The Hoopla album, so I’ll force myself to get back on track.

Pete and I had no songs on that album. At that time we were knee deep in Central American issues like the genocide in Guatemala and the hordes of refugees needing help. Bill Graham had agreed to help Pete produce a fund-raiser to aid the 500,000 Mayans and Salvadorans who were cooped up in a camp in Southern Mexico, with Typhus and Dysentery and dirty water and starvation killing them every day. We’d written a song called One More Innocent about the fact that America was supporting the dictators who were killing their own people and displacing even more. The chorus line started: “Every time we close our eyes, one more innocent dies, every time we believe the lies, one more innocent dies…etc. (You can hear it on the Watchfire album or Ernesto Brown’s version)….

Pete wrote Reggae type music—very beautiful and catchy too…so catchy that the pop producer, Peter Wolf (NOT the singer!) decided it could be a hit song and that the lyrics needed to be changed…too depressing. Pete called me from the studio, asked me to come in and talk about it. Grace liked the song as it was and would have sung it. Mickey wanted to change the lyrics to One More Innocent Lie—about a guy being unfaithful to his girlfriend and telling her a lie to spare her feelings…or something like that. A huge argument ensued about what rock n’ roll is, with one famous rock star from another band adding his two cents, “Rock n’ roll is about having a good time, baby, and that’s all people want to hear—not depressing shit!” Pete and I countered by quoting Bob Dylan, George Harrison, and any other songwriter’s lyrics we could think of that contained social change content, but it fell on deaf ears. Grace agreed with us, but at that point Mickey had all the power. The record company considered his voice “commercial” (don’t forget it was the eighties), almost as high as Michael Jackson’s, and capable of churning out mega-hits. Peter Wolf (also backed by record company power) wanted top ten hits—never mind that there were 500,000 refugees depending on the song revenue (we were going to donate our writer’s royalties to them) and the proceeds from the concert that Bill Graham and Pete were going to produce in tandem with the song’s release (Jerry Garcia had already agreed to participate). The upshot was that Pete withdrew the song and didn’t submit any others.

There—I got it out—Pete had absolutely nothing to do with the decision to take the band pop! He hated it and felt that although the band might have top ten singles, they would lose their gigantic concert-going audience. He brought up the Grateful Dead as an example of a band that didn’t have top tens, but drew a large (ever-growing) audience. The record company reps didn’t want to hear it.

You have to understand that it wasn’t just Starship that was changing during the eighties. The record companies had been bought up by multi-national conglomerates that had no real interest in music—only in the money to be made from it. Records and songs had become “products.” The A&R men the band had a relationship with had been fired—replaced by businessmen who didn’t know shit about music, and cared even less.

After Pete left Starship, he made a concept record called Watchfire, using old-fashioned techniques and instruments—basic tracks, real drums (Mickey Hart, Babatunde Olatunji), mandolin (David Grisman), guitar greats like John Cipollina and Jerry Garcia, etc, etc, etc. I wrote almost all the lyrics. One of the songs, Guatemala, was made into a music video that is still being used by Amnesty International for their fundraisers.

One of the songs on Watchfire pretty much sums up our feelings about the direction our country was taking in the eighties: “I see greed like a shadow, darkening this land, we’ve sacrificed much more, than we understand, built a future on sinking sand…”

Having said all this, I guess I should mention that there was much to love in the eighties, too. Pete and I were raising our beautiful children, our relationship continued to be amazing, we were surrounded by friends, old and new, who inspired us, and there were certainly a lot of artists who carried on putting out good music. And, in spite of it all, I have to admit to finding We Built This City kind of fun…catchy like a commercial, fun to dance to, go a little crazy to—and watching the Muppets (in the recent Muppet movie) dance to the song as they rebuilt their studio had me falling out of my seat from laughter.

We Built This City: Great storyteller, the history of Starship, you and Pete. Everyone does have something unique to offer, if often they’d only give themselves a good chance.

Fascinating stories, thanks so much for sharing!!

Thank You, Jeannette. Though Pete hated it, that was a cool bass sound. Thanks for explaining how it was done.